by Paula Marcoux.

Once upon a time, in my town of Plymouth, there was a charmed island kingdom, peopled with capable, active and humane residents. Fishers and farmers, the islanders lived by the tides, the sun, and the wind. Lore-keepers, they knew and could tell the story of the place, its pastures, trees, and waters.

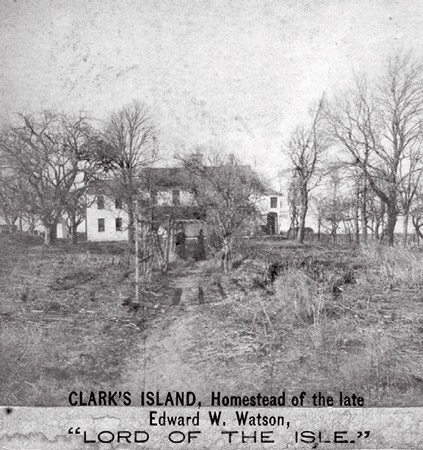

This magic place and time—Clark’s Island, mid-nineteenth century—was ruled, some would say created, by a benevolent, wise and humorous individual called Uncle Ed Watson. Along with his brother, and then his nephews, he built a fiefdom of garden, field and meadow, marsh, bay, and clamflat. None of us alive today will ever get to bask in the “sterling goodness” and “imperishable romance” of this extraordinary neighbor—he died in August of 1876—but the glow of this man’s spirit infuses the writings of period eyewitnesses. An exemplary host, Edward Winslow Watson was famous for offering hospitality—if necessary even involving a rescue at sea—to friends and strangers alike. The beneficiaries of Uncle Ed’s generosity left accounts of their island visits revealing that they were unanimously bowled over and inspired by the experiences.

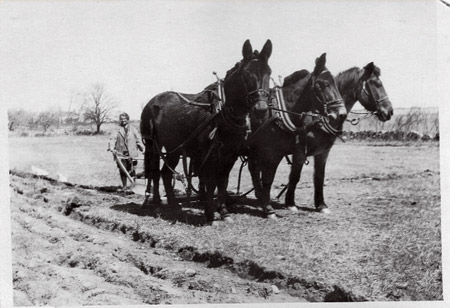

An unidentified woman plows a Clarks’ Island field with a team of two horses and a mule, circa 1930.

In particular, one of my favorite informants, Henry David Thoreau (also one of the stranger strangers to habituate the island in the 1850s) betrays a comfort in that environment that was elusive to him in much of the rushing, hypocritical, pious, money-grubbing “real world” that he rejected. He also wisely used his time there to increase his familiarity with tides and boating, and to up his general saltiness and handiness quotient. Reading between the lines in Thoreau’s journal I can almost feel Uncle Ed’s kind, bemused indulgence toward the young transcendentalist. A few lubberly mishaps were not enough to keep the Watsons from enfolding Thoreau into the daily routines of island life during his visits.

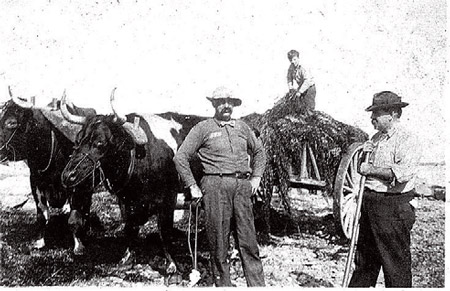

With the help of a yoke of oxen, two Taylor men and an unidentified boy harvest kelp for fertilizer from the shore of Clark’s Island, circa 1910.

Generous with easy competence, Edward Watson taught by graceful example all the things one needed to know to live on the island—how to swim horses across from the mainland; how to interpret the arrival of every bird, fish, and fly; how to simply put aside trappings of conventional life—like shoes, for example—when superfluous. Intellectually engaged and socially alive, he read widely and followed world politics in the journals of the day. He thought nothing of skipping up the coast in his island-built, green-bottomed, lapstrake boat to hobnob with Daniel Webster at his Marshfield home, or to take the celebrity senator on a fishing trip down off Manomet.

To a degree that is all but unimaginable to most of us today, the big old house on the island was full to bursting with the Watsons’ friends, and their friends, for three seasons of the year, essentially for three decades. The entertainments described by visitors were varied and shifting, depending on the tastes and talents of the personnel: music and dances, old-fashioned cooking projects, new-fangled sports like croquet, and above all, poetry and ideas. We read of wandering among Uncle Ed’s flower beds and fig-trees; of sharing the cherries and berries with the birds that loved them (Uncle Ed maintained a no-shooting rule in his garden and orchard); of sailing and rowing and singing under the moon; of observing horseshoe crabs mating in the shallows; of botanizing on the hillside, watching the sunset from the high rock and just generally enjoying the goodness and beauty of being alive.

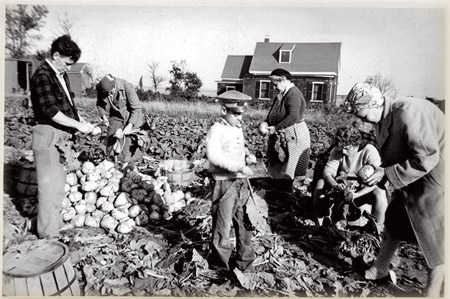

Harvesting Clark’s Island’s signature turnip, circa 1940. -Image courtesy of William Watson Taylor, Jr.

Putting aside the “imperishable romance” for a moment and recalling that I am a food historian by trade and a skeptic of human nature by inclination, I must only marvel at the level of self-sufficiency of the Watson operation. Where most people living on an island four miles from town would see their boats as a supply lifeline, the Watson family used them to transport and sell their production surplus. They raised cattle, sheep, hogs, and poultry, including geese and guinea hens. They sold fish and lobsters in Plymouth and took out fishing charters. They exported hay and lumber, and sold some of the produce of their singular orchard and garden (including a famous island-bred turnip, judged critical for the most authentic Plymouth Succotash, and now extinct).

How many people in this life create a kingdom that is an extension of self—of “an absolute purity that was neither austere nor fastidious” (to quote Uncle Ed’s epitaph)? Only a human who was energetic, fearless, and kind, and who was lucky enough to be born in exactly the right place at the right time could achieve all that, and still show his doubts, as in this undated poem of his:

Dear Jennie,

that nice cranberry tart

You gave to me bedecked with paste

Lies like a bleeding, broken heart

Whose inner life has run to waste.

You placed it on the basket top,

In paper coverings still it lay,

Mid rolling seas a lurch it got.

And bled its inner life away.

Its fate, how like the buoyant heart

That o’er life’s billowy ocean springs

Till disappointment tips the bark,

And overstrained, snap go the strings.

This surprising image—the broken cranberry tart, a tender gift, paper-wrapped for the island passage and mortally injured—is vividly poignant, at least to a dedicated pie-baker. I’m no poetry expert, but I doubt many poets of the period were so fearless as to compare the human spirit to any species of pastry.

But it certainly works for me.

Can we be nostalgic for a place and time we never experienced? Is it wrong to miss people we have never met? For me, cooking and eating a recipe from another era narrows history’s unbridgeable time-gap and lets me feel I’m peering just a little bit into that elusive other side. -Paula Marcoux

Cranberry Tarts in Puff Paste

By the 1850s, the phrase “cranberry tart” was almost always preceded by the phrase “old-fashioned”, which may explain why at midcentury literary and casual references outnumber recipes. Fashionable cookbooks relegated them to plain home dinners—never for company—as early as the 1830s. This version is put together from various simple period renditions. The pastry formula is based on one in the notebook of Clark’s Island regular, Mary Russell Watson (whose husband Benjamin Marston Watson bred the famous turnip).

You may choose to make both the filling and pastry ahead and store in the fridge up to two days before forming and baking the tart, if convenient.

Filling

- 3 cups fresh local cranberries

- 2 cups sugar

- ½ cup water

Place all ingredients in a medium saucepan over medium heat. Bring to a simmer and cook five or ten minutes, or until berries have exploded and made a sauce. Put aside to cool thoroughly before making tart.

Pastry

- 10 ounces unbleached white flour

- ¼ teaspoon salt

- 8 ounces cold butter, cut in bits (or half lard)

- ½ cup ice water, approximately

You may use a large wooden bowl with a crescent-bladed hand chopper, as in mid-nineteenth-century Plymouth, or a food processor. Place the flour and salt in the bowl and chop in 8 ounces of fat until the flour looks like coarse meal. (If using the food processor, pulse 12 to 15 times.)

Add the water, holding back a few drops, tossing the dough with a fork or knife until lumps cling together. Quickly push them into a ball, adding more drops of water to the dry parts if necessary. If using the food processor, pulse quickly, and stop and push dough together with a fork or knife, rather than letting the machine work the dough at all. Once it’s all in a ball, cut it in two and wrap each ball of dough tightly in plastic wrap and store it airtight in the fridge for at least 2 hours.

To construct and bake

- a nutmeg, optional

Preheat oven to 375 degrees.

On a lightly floured surface with a lightly floured rolling pin, roll out one of the balls of pastry to an even 1/8th-inch thickness. Transfer it to a 9-inch pie plate, and fill with the cool cranberry sauce. Grate over nutmeg, if you feel like it.

Roll out the other half and simply use as a sheet (with a hole cut in the center) for the top crust. Or cut it into strips and apply as a lattice or “bars”, for the top of the pie. (There are period examples of both treatments, as well as pastry leaves and flowers and curlicues and even “mottos” or the initials of the tart’s recipient. Not to mention baking circular or triangular cranberry tarts in puff paste without pans. As the poet says, “bedecked with paste”, right? So go crazy.)

Crimp the edge of the pie to seal, and bake 50-60 minutes, or until filling is bubbling in the center, and the pastry is golden brown.

Makes 1 9-inch pie.

The wistful Paula Marcoux regrets that she did not have the forethought to move to Plymouth in 1837 (instead of 1987), as that would have enabled her to meet some of her favorite town denizens and visitors, now long deceased. Nonetheless, she is grateful for the current generation; Jim Baker especially comes to mind for his clutch assistance in finding period images to illustrate this column. Thanks also to Skip Taylor for permission to publish some of his family’s treasures.