by Paula Marcoux.

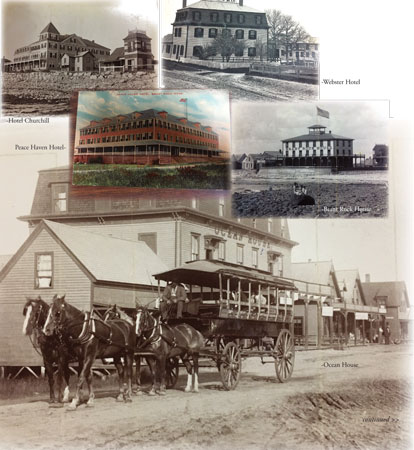

In the decades following the Civil War, middle-class Americans discovered summer vacation, departing towns and cities to breathe health-giving salt air and to perhaps even try sea-bathing. Resort hotels and rental cottages sprung up in former fishing hamlets where a farmhouse with a spare room had heretofore been the only lodging afforded a traveler.

Marshfield Hotel Photo Attributed to L.B. Howard

Courtesy of Marshfield Historical Society with a special thank you to Dottie Melcher.

Brant Rock and her Summer Resorts

In Brant Rock, this trend really took off with the extension of the Duxbury and Cohasset Railroad to Marshfield. (The “last mile” between the depot and the resorts spurred enterprising local farmers to hitch up their “barges”—big wagons with benches—and diversify into the transportation business.) An 1878 guidebook published by the Old Colony Railroad assures potential visitors that “a party can select from the abundant hotels at Brant Rock to suit their circumstances or tastes.”

As to activities in Brant Rock, the same guide recommends “the beautiful beach at Brant Rock, … affording as it does such excellent opportunities for sea bathing”. The author continues: “There are probably not outdoor sports more fascinating, while visiting our shores, than that of boating and fishing on the beautiful inlets and rivers along the coast in this vicinity, the smooth waters being especially adapted to ladies of a timid disposition, while those of a more venturesome inclination will find the broad Atlantic, with plenty of sea room, inviting them to its rolling surface.”

As tourists transitioned to “motoring” in the early twentieth century, South Shore summer business blossomed for a time, and then was eclipsed, as vacationers, untethered from the rail lines, discovered Cape Cod, New Hampshire, and Maine. Prohibition and the Great Depression were unkind to Brant Rock as a destination, and one by one the big hotels went under.

Rest and recreation… and shore dining!

A big part of restoring the body’s health was linked in the nineteenth- century mind to stimulating the appetite. One of the benefits ascribed to outdoor activities was that they sharpened one up for a really good meal. Then, as now, tourists gravitated to the local specialties, like shellfish and chowders.

And there were those who went charter fishing with the anticipation of a great day on the water followed by the treat of eating truly fresh fish. One late summer/early fall favorite in this department was the bluefish—not surprising because it is one of the best-fighting and also the worst-keeping fish in our region. Fish-lovers knew that it had to be truly fresh and well-handled to be at its best; the idea of ordering it at a restaurant out of sight of water was a non-starter. But catching one’s own did not guarantee a bargain. As one sports travel writer put it in 1888, “In the course of a Summer fishing cruise the cost of a single blue-fish to the amateur and average city sportsman will range from three to thirty dollars per pound in actual money for yacht-hire, stores, equipment, ammunitionable necessities, to say nothing of the time spent, the clothes ruined, and the fingers torn. But to the true sportsman who knows his business … blue-fishing is an excitement, a delight.” (Um, yes, his estimate of $3 – 30 per pound, while perhaps jocular or hyperbolic, was calculated in 1888 dollars. I leave it to the economics student to extrapolate those numbers to today’s cash value…)

Paula Marcoux, food historian, blames her sharp appetite on the sea air surrounding her Plymouth home.

BROILED BLUEFISH WITH SWEET-PEPPER BUTTER